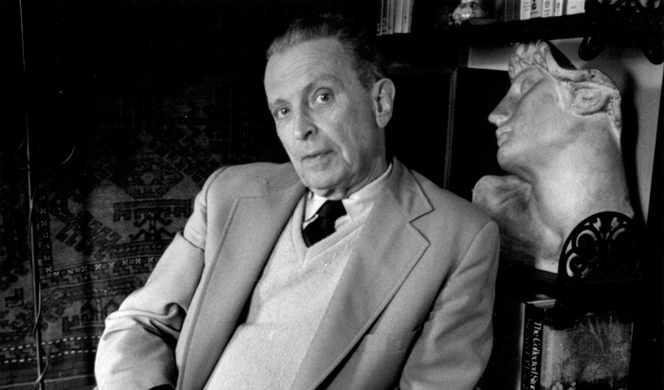

Though James Farl Powers (1917—1999) focused his fiction on a variety of subjects, he is best known for his depictions of Catholic priests. This unique gift is particularly evident in his novel, “Morte D’Urban”, and in several of his short stories.

“Morte D’Urban” concerns the spiritual transformation of a priest who is overly preoccupied with the things of this world. The protagonist, Father Urban, is an ace on the golf course and a popular preacher, and if a new church needs to be built, he is the one who can raise the funds. The latter attribute involves him with a character named Billy Cosgrove. Billy is no Al Capone, but he is a corrupting influence all the same. Father Urban’s eventual revolt against Billy’s evil is a moving and pivotal episode.

Readers unfamiliar with Powers’ work should not expect anything resembling “The Thorn Birds”. Urban’s comical odyssey does include various temptations, but the author steers clear of every cliché. During a potentially dangerous encounter with a woman named Sally, Urban sinks into a mildly intoxicated daydream. It is an artfully rendered prose-description of what might have been, not necessarily what should have been. Powers portrays Urban’s rejection of Sally’s advances with cool-headed restraint and realism.

Flannery O’Connor described the Catholic characters of Powers as “vulgar, ignorant, greedy, and fearfully drab”. Then, with her usual clear-sightedness, she added: “Mr. Powers doesn’t write about such Catholics because he wants to embarrass the Church; he writes about them because, by the grace of God, he can’t write about any other kind. A writer writes about what he is able to make believable.”

Father Ernest Burner is a classic example of such a character. He is the protagonist in a short story called “Prince of Darkness”. Burner is an overweight, discontented forty-three year old curate who dreams of having a parish of his own. But the expectations and hopes that were attached to his priestly calling never seem to pan out: ‘He was the desperate assistant now, the angry functionary aging in the outer office. One day he would wake and find himself old, as the morning finds itself covered with snow.’ The handling of such a character by any other writer would result in gloom. But Powers transforms the crude material of Father Burner into something enjoyable.

The same protagonist is present in “Death of a Favorite” and “Defection of a Favorite”, and these two stories are told from the perspective of a rectory cat! The droll and observant feline, whose name is Fritz (no relation whatsoever to the film character, “Fritz the Cat”), has an antagonistic relationship with Father Burner. But there’s a special providence in the actions of a cat; thus things work out all right for both Fritz and the curate.

These three short stories—plus “Morte D’Urban”—represent J. F. Powers at his very best. And where the Catholic clergy is concerned, I doubt that it’s possible to read anything more intelligent, humorous and true to life.