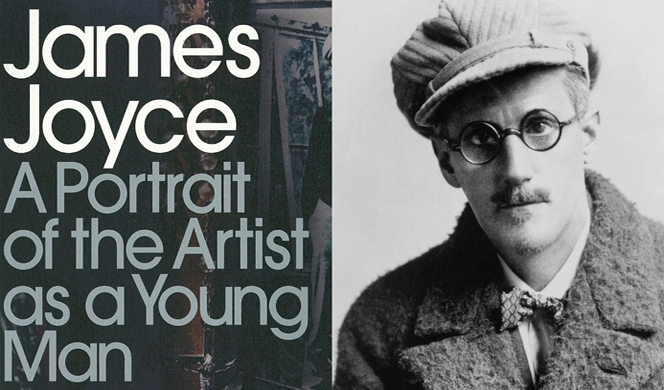

James Joyce (1882—1941) was one of the greatest literary geniuses of the twentieth century. He wrote “Dubliners”, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”, “Ulysses” and “Finnegans Wake”. My favorite of the four has always been “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”.

The protagonist of the latter is an Irish Catholic youngster named Stephen Dedalus. The plot is focused on the development of Stephen’s mind, from childhood to young adulthood, and his eventual rejection of Catholicism in order to pursue a life of creative fulfillment abroad.

The first part of the novel concerns Stephen’s life at a Jesuit-run school. He is depicted as a studious, observant, and physically timid boy. The descriptions of this world are evocative, realistic, and sometimes harrowing—as when Stephen receives a dose of undeserved corporal punishment from the prefect of studies. He realizes early on that he is different from others, and he foresees for himself an eventual transformation: ‘Weakness and timidity and inexperience would fall from him in that magic moment.’ Later, during adolescence, he becomes obsessed with sex. But this passion for pleasure is squelched when he and his fellow students listen to a sermon on hell during a retreat.

This sermon has had a strong impact on many readers over the course of the last century. Anthony Burgess wrote: ‘I still find it difficult to read the hell-chapter without some of the sense of suffocation I felt when I first met it…’ I too was unnerved by the hell-chapter, but it also impressed me with its sheer power. About fifteen pages are devoted to the sermon, and I doubt that any writer but Joyce could pull it off without lapsing into caricature. The point of this terrifying episode is to dramatize what his protagonist is up against. His rejection of the Church must emerge from this crucible of fear.

Stephen’s apostasy is as unique as it is profound. He remains more a student of Thomas Aquinas than of any secular master. And to quote Anthony Burgess again, where he speaks of Joyce’s work in general: ‘Despite all the mockery and blaspheming, it is safe to put Joyce’s works into the hands of the devout believer … The Church stands that it may be battered, but the fists that batter know their own impotence.’

Near the novel’s end, Stephen is engaged in a climactic dialogue with a friend named Cranly. They debate the pros and cons of Stephen’s resolve to leave his family, country, and Church. In a sense Cranly is Catholic Ireland, or so he has always seemed to me; and as such I identify with him, sympathize with him, over and above Stephen Dedalus.

Even so, Joyce’s protagonist—the prime example of anti-religious rebellion—deserves the serious consideration of all thoughtful readers.